Published August 11, 1974

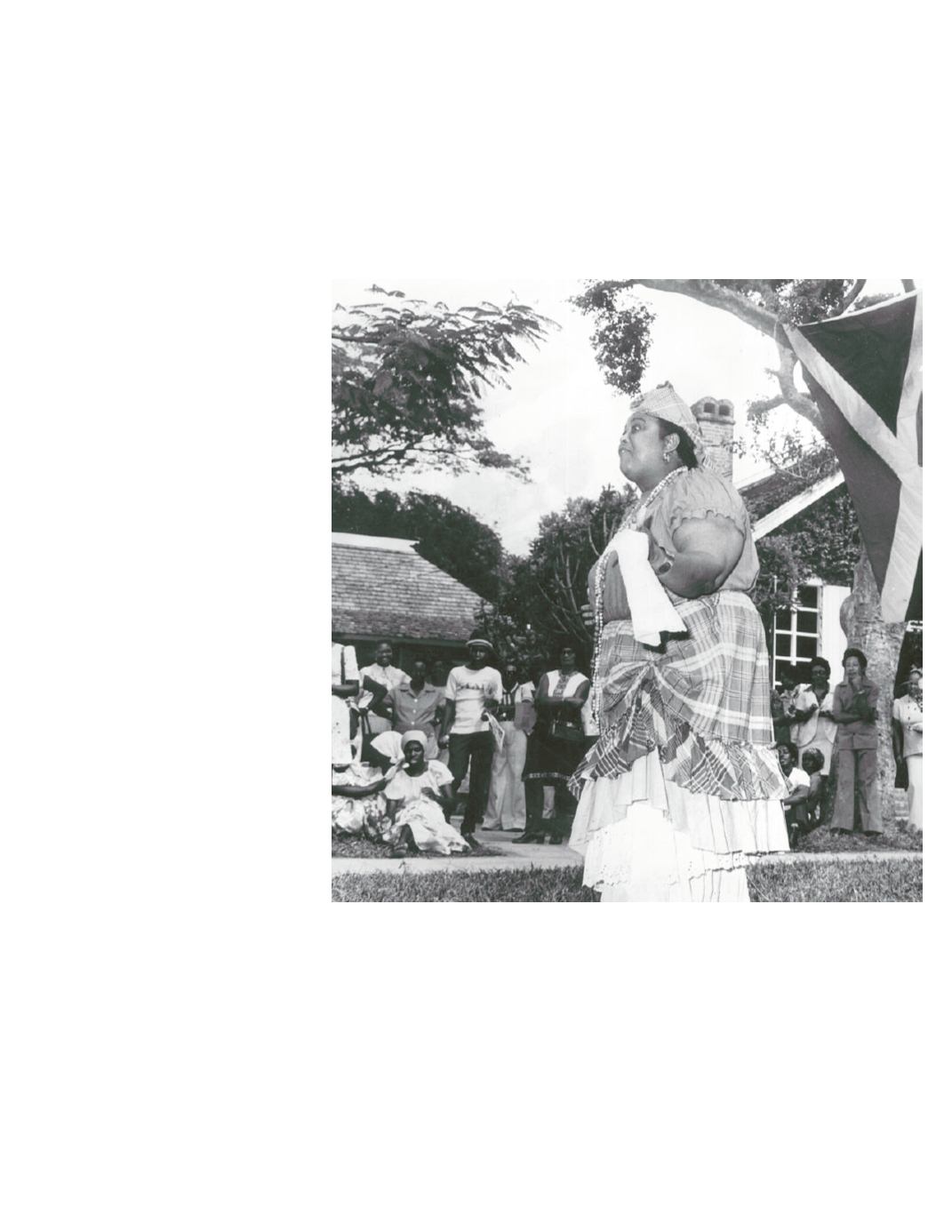

Louise Bennett:

Our well-Known, well- loved poet

By George Panton

T

HE AWARD of the Order of Jamaica

“to Louise Bennett is one in which

all lovers of the arts (and especially

the P.E.N. Club) take special pride. One of

the best-known and most popular persons in

Jamaica she has not only brought pleasure to

scores of thousands but she has also demon-

strated that poetry is not something esoteric

which few can understand and appreciate.

Her “Jamaica Labrish” was a best-seller and

after the sale of several thousand copies of

the 1966 edition a second impression had

to be produced in 1972. The hard-covered

edition has been completely sold out but a

paperback is still available in the bookshops

($2.50).

The printed word is merely a record of

Miss Lou’s writings and is known to but

a small fraction of the numbers whom she

has delighted from the stage or through the

medium of TV and radio. Nevertheless it is

mainly on that aspect of Louise Bennett that

this short profile concentrates in keeping with

the current series of Arts Profiles.

We all laugh at Monsieur Jourdain in

Moliere’s “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme” who

expressed his astonishment “at learning from

his professor of philosophy that he had been

talking prose all his life. But many in Jamaica

laid themselves open to similar laughter at

not appreciating for a long time that what

Louise Bennett wrote was poetry. And this

included several critics, it being notable that

the “Independence Anthology of Jamaican

Literature” published in 1962 included poem

of Louise Bennett’s but placed it (along with

an Anancy story—she being the only person

to be represented both in prose and in poetry

in that book) under the Miscellaneous sec-

tion, a hodgepodge of autobiography, history,

folk-lore and humour.

Acceptance

But there were some percipient persons,

notably Mervyn Morris, himself a highly

respected poet, who took a different point of

view and stressed that, the humorous verse

despite (or because of?) its being written for

delivery from the stage was indeed poetry. He

set out this idea at some length in a series of

four articles which appeared on this page of

the Sunday Gleaner in the four weeks of June

1964. The dialect had made the middle class,

the one which read poetry and in fact did any

reading at all, regard the poems with suspi-

cion, if not condescension.

But Morris wrote: “We have moved

gradually from an unthinking acceptance of a

British heritage to a more critical awareness

of our origins and a greater willingness to ac-

cept the African elements of our past as part

of our national personality.”

This acceptance has now become almost

an insistence and no longer needs to be

stressed. But Louise Bennett had demon-

strated this long before the “culture vultures”

saw it.

Publications

In addition to the dialect, there was the

perhaps unvoiced suspicion that humour

was not the subject of which poetry could be

made and therefore Miss Bennett’s entertain-

ments had to be labelled as no higher than

verse. This idea, has now disappeared and it

is accepted that humour is poetry in a vivid

means of conveying satire or irony. Clearly

the poetry of Louise Bennett held up a mirror

to many of our foibles and forced us to laugh