Herbert Gayle

Contributor

What must change

I

N THE 2007

Forced Ripe Report

(Gayle

and Levy), young men in three different

inner-city and working-class communities

stated that the police could not protect them,

when “in reality, they need protection from

us”. According to the young men, “The

police can protect women and children, and

middle-class people, but not us. Is a war

thing between us.”

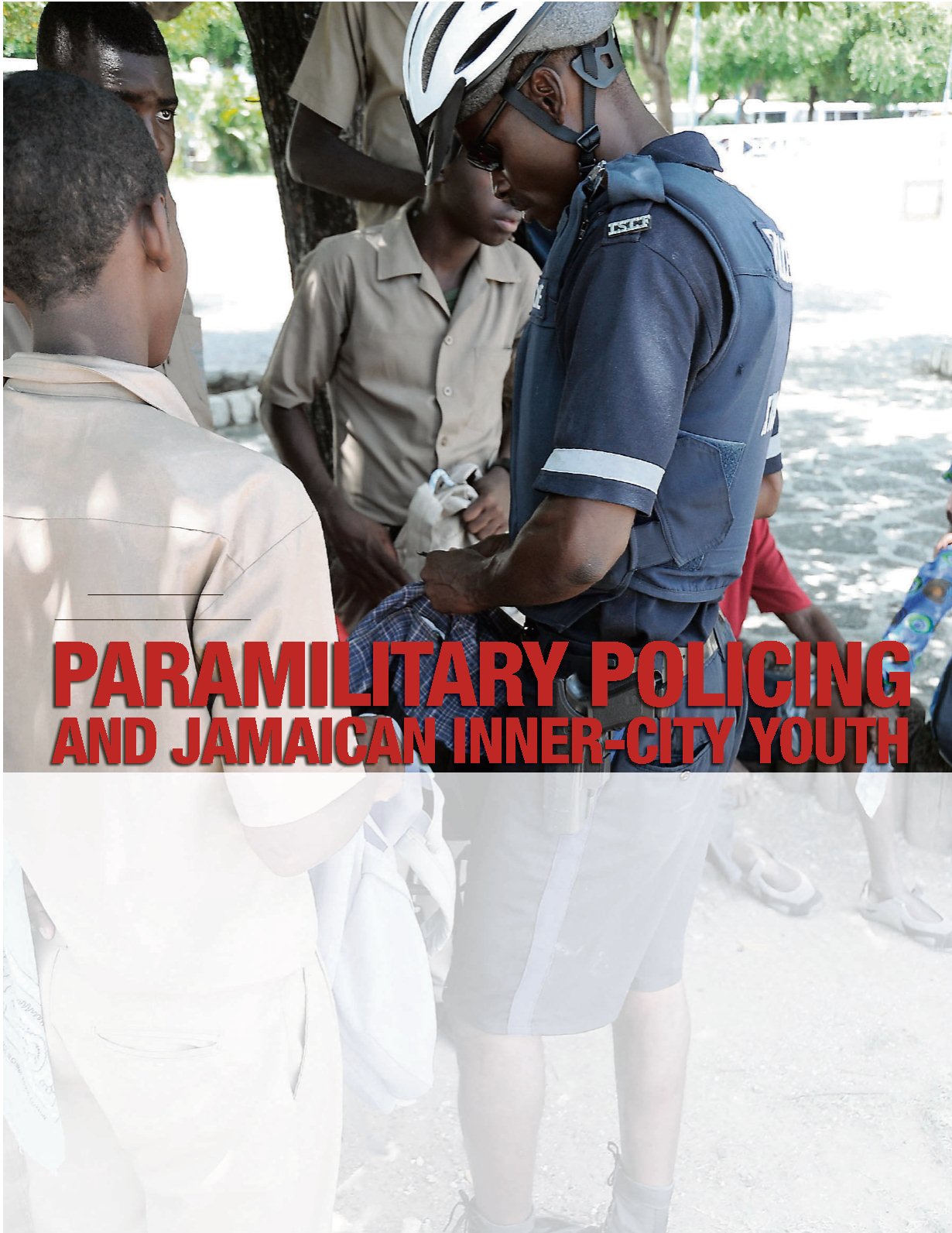

In Jamaica, police work climate, policing

style, and the treatment of the police and

inner-city youth by society contribute to a

disastrous relationship between police and

young men. The situation is a recipe for

civil war in which both the State and inner-

city males suffer high casualties.

Policing is one of the most hazardous pro-

fessions in the world. More than a half of all

police deaths are usually accidental, with

road fatalities, drowning, and burning rank-

ing among the most frequent. Nonetheless,

in the most violent countries, the majority of

slain police officers are usually murdered,

suggesting a difference in policing policy

and process, as well as an aggressive youth

attitude towards the police.

In New Zealand, one of the most peaceful

countries in the world, only four police officers

were killed by criminal acts between 2000 and

2011. This produces a police death rate by crimi-

nal acts of three per 100,000, compared to 150

per 100,000 for the same period for the Jamaican

police. Over the same period, Jamaica’s average

homicide rate was 50 per 100,000; but 350 for

inner-city young men (15-34 years) in the

Greater Kingston area. This rate is almost twice

the rate of deaths (205 per 100,000) in the Iraqi

War and Occupation of 2003 to 2011. Not sur-

prising, the police killed an average of 200 young

men per year for this period – and on average, 13

officers were killed yearly.

EXTREME FEAR

Societies with homicide figures above the

civil-war benchmark (30 per 100,000) such

as Jamaica and South Africa have so much

violence that policing is characterised by

extreme fear. In such settings, an officer’s

preoccupation often shifts from that of pro-

tecting others to that of protecting himself.

In New Zealand, England and most other

stable societies, the average police officer does

not carry a gun on his person. In these coun-

tries, lethal weapons are carried concealed in

service cars, or are carried by various special

strike forces called upon in events of emer-

gency or extreme violence. In countries such

as Jamaica and South Africa, policing is done

as if the countries are in a permanent state of

emergency. Officers are armed with hand guns

and sometimes assault rifles and are psycho-

logically locked in a state of war-readiness.

PUBLISHED:

FEBRUARY 1, 2017

There are many

Jamaicans who

support the police

and youth killing

each other. We

ascribe a value to

the lives of both

inner-city youth

and frontline

police, both of

whom are unfortu-

nately from the

underclass. ... We

treat the death of

anyone from the

merchant class as

a catastrophe, but

the death of a

peasant with

indifference.

“

”