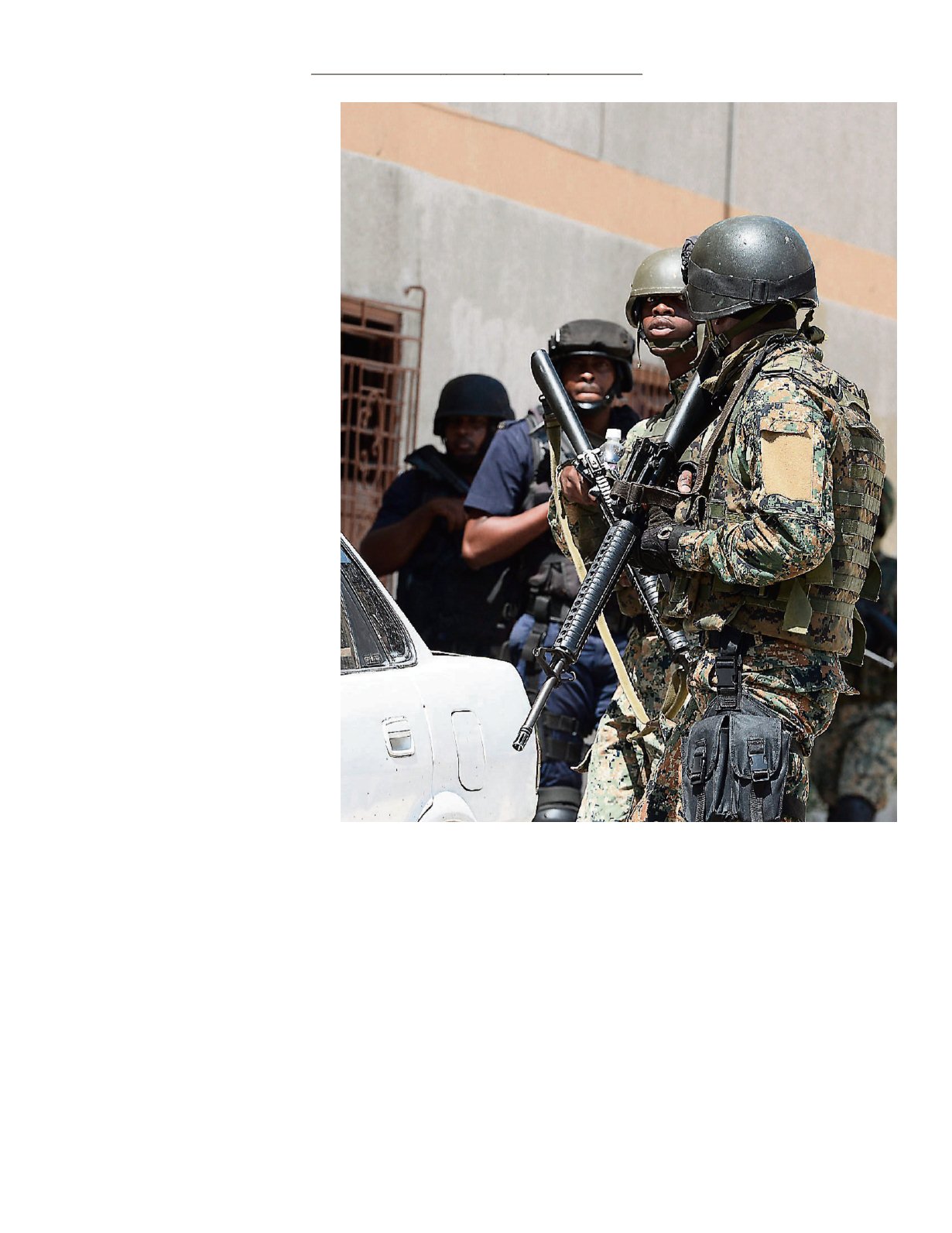

Part of the danger that police officers face

rests in the structure and original purpose of

the Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF) that

many in the society are slow to change.

From the Victorian period to the present,

the British used the police as the most visi-

ble symbol of colonial rule. The structure

has been a blending of military and civilian

roles into one police service. With the

establishment of the Metropolitan Police in

London in 1829 came a shift from military-

to community-style policing as the primary

way of dealing with social order. The many

police forces formed in the colonies in the

19th century were not allowed to model the

New Police in England.

In the late 1990s, the JCF started to make

an obvious shift away from reactive, para-

military responses to crime and disorder and

began to openly embrace community-based

policing. Nonetheless, there has not been

enough of a culture shift within or outside

the JCF to significantly reduce the depend-

ence on deadly force.

Every country has a measured policing

efficacy; and usually, this is by conviction

and/or clear-up rates. In this article, we

examine the relationship between the clear-

up rate and murder rate between 1960 and

2007 for Jamaica. It is fair to expect a coun-

try to clear up at least 50 per cent of its mur-

ders. However, this is not always possible in

certain unstable environments. The data

allow us to make three conclusions that are

comparable with trends in other high-vio-

lence Caribbean countries such as Trinidad

and Belize.

First, there is an almost mirror-perfect

inverse relationship between clear-up and

murder rates – as murders increase in num-

bers, the capacity (especially if unchanged

in tooling and operation) to clear up murders

falls with comparable velocity.

STRUGGLE TO CLEAR UP MURDERS

Second, most security forces struggle to

achieve even the base clear-up rate of 50

per cent once the murder rate exceeds the

civil-war benchmark of 30 per 100,000.

The dataset shows that just before

Independence, the homicide rate was below

five per 100,000, comparable with the

world’s average; and hence the country had

a clear-up rate above 95 per cent.

Independence usually comes with unrealis-

tic demands from the populace and politi-

cal struggles to seize leadership. Our tran-

sition was problematic; we quickly became

segmentary factional – Comrades versus

Labourites. Within 10 years of

Independence, our murder rate jumped

beyond 10 per 100,000 and the clear-up

rate dropped dramatically below 70 per

cent. Nonetheless, up until the political

tribal war of 1976-1980, national security

was able to achieve at least the minimum

50 per cent clear-up rate.

In 1976, Jamaica’s homicide rate was 20

per 100,000 with a clear-up rate of 62 per

cent. The following year, the homicide rate

climbed slightly to 22 per 100,000 and the

clear-up rate slipped to 52 per cent. In the

middle year (1978), homicide stabilised

somewhat at 21 per 100,000, and the clear-

up rate climbed back correspondingly to 54

per cent.

The following year (1979) can be

described as the calm before the storm.

Homicide dropped to 19 per 100,000 as

political activists and party-aligned gangs

watched and planned for the upcoming elec-

tion. Then came the ‘War of 1980’ in which

over 800 Jamaicans murdered each other,

resulting a homicide rate of 48 per 100,000.

As we jumped across the civil-war bench-

mark, the clear-up rate took a dive to an

embarrassing 37 per cent. The shock of our

tribal war, and the absence of a competitive

general election for a decade rescued our

social sanity. However, by 1995, we had

again crossed the civil war benchmark, and

only for single exceptional years (1999 and

2003) have the clear-up rates exceeded 50

per cent.

The Jamaica

Constabulary Force

is dependent on

deadly force

PUBLISHED: FEBRUARY 1, 2017