T

O UNDER-

STAND the seri-

ousness of the

homicide problem among

the combatant age of the

male population of our

inner-city communities,

we shall compare these

figures with Iraq at full-

scale war. A 2013 study

(Mortality in Iraq

Associated with the

2003–2011 War and

Occupation: Findings

from a National Cluster

Sample Survey by the

University Collaborative

Iraq Mortality Study)

calculated that there were

about 461,000 war-relat-

ed deaths in Iraq during

the US-led invasion of

2003 to 2011. This

means an average yearly

death of 57,625. Using

the estimated average

population of 28.17 mil-

lion for the period, we

can calculate that the

war-related homicide rate

was 205 per 100,000.

Notice that at 405 per

100,000 for combatant

aged males in the KMR,

the death rate was almost

twice higher than that of

Iraq at

full-scale war.

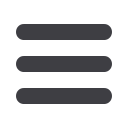

The figures show that

Jamaica has an ‘unde-

clared civil war’ between

gangs, and between

gangs and the State. The

data over the last 16

years show devastating

results from these wars –

a kind of social suicide.

Basically, we are killing

ourselves. Let us now

examine the side of the

State. Between 1989 and

1999, the police death

rate was 112 per

100,000. This increased

to 154 per 100,000

between 2000 and 2010

before the ‘Tivoli

Incursion’. These figures

are among the worst in

the world and show that

the State is taking a

heavy toll. In countries

such as New Zealand, the

police homicide rate is a

mere three per 100,000 –

that is 51 times less than

for the Jamaican police.

In New Zealand and

Europe, police can con-

centrate on community-

style policing; in

Jamaica, the police

remain in war-readiness

mode – and emotionally

hold on to the protective

frame of paramilitary

policing. This style of

policing continues to

feed the anger in the

inner cities, which helps

to fuel gang formation.

However, no one in

charge of the police dare

say put your weapons

away when the officers

are so washed with fear.

Major changes must

come at some point, and

come soon.

(See Figure

2)

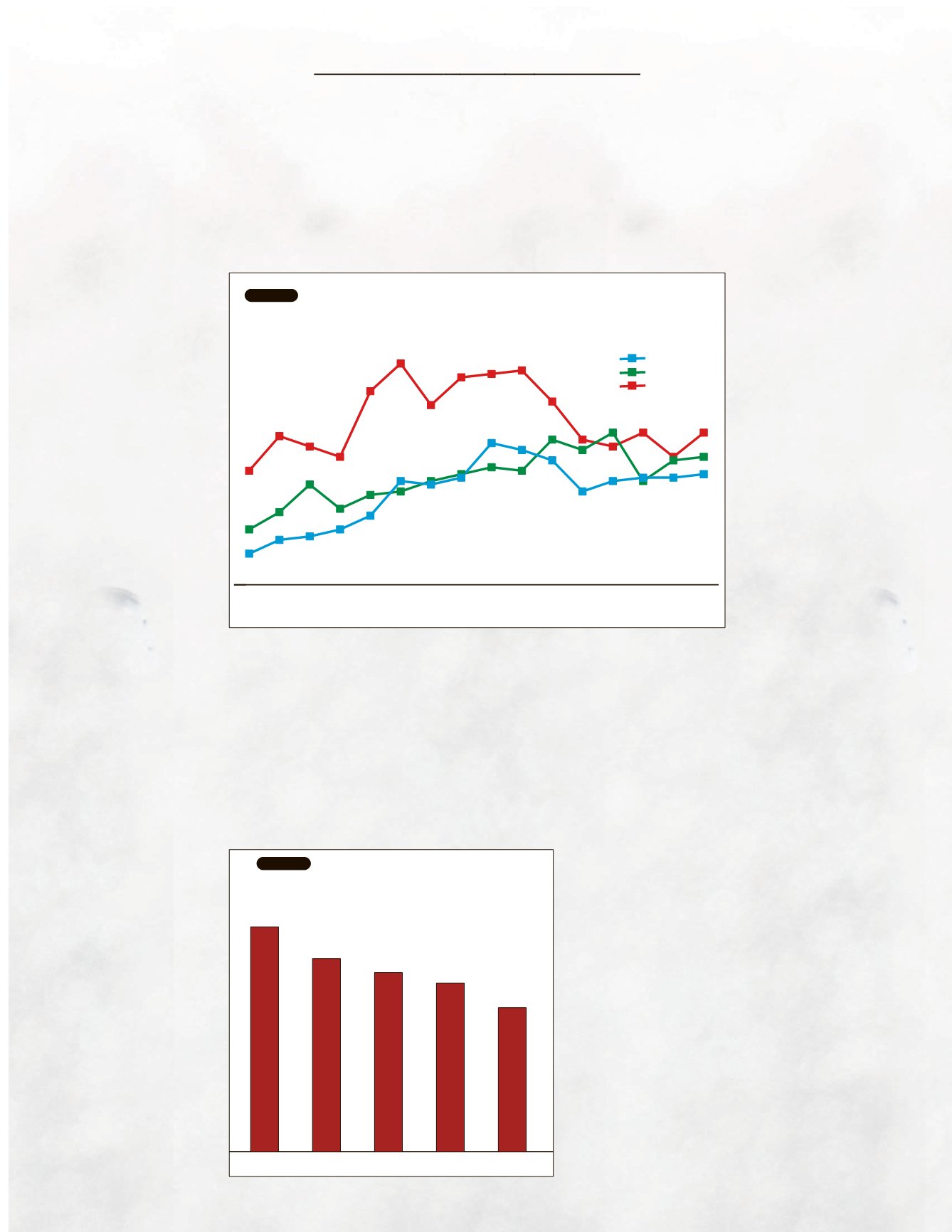

CAUSES OF HIGH

MURDER RATE

Since the start of the

new millennium, Jamaica

has had the fourth high-

est average murders in

the world. This is the

result of centuries of

oppression, combined

with decades of political

warring. In the work of

violence experts, a histo-

ry of violence is of criti-

cal importance to the

construction and mainte-

nance of feud or inces-

sant warring.

Anthropologists of social

violence are usually con-

cerned with two broad

sets of impact caused by

a history of violence:

adaptation to violent

ecologies, and socialisa-

tion and social organisa-

tion around the effective-

ness of violence.

The ability of the

human species to adapt

to environments is well

documented; but the

work of Dawkins (1976)

is critical to our under-

standing here of how

aggression is critically

necessary for our sur-

vival, and how each

group of persons pass on

the variant gene that has

the greatest advantage

for survival in a specific

environment, including

violent ones. In other

words, the efficacy of

violence is now in our

genes. We know how to

use it to achieve political

and economic ends, and

even to end domestic dis-

putes. The figures below

(Figure 3) show that

while the Tivoli

Incursion had done much

to restore some power in

the state’s apparatus,

murders have simply

been fluctuating.

Violence is a by-product

of social ills. In Jamaica,

we have many, ranging

from social injustice to

exclusion from basic

education. There is

urgent need for the

trained, the brave and

policymakers to sit down

to discuss the way for-

ward.

Honduras El Salvador Venezuela Jamaica Colombia

64

55

51

48

41

Top-five countries with highest average murder

rates since year 2000

FIGURE 2

9

16

33

43

40

37

56

64

52

60 61 62

53

42

39

44

37

44

21

29

22

26

27

30

32

34 33

42

39

44

30

36

37

13 14

16

20

30

29

31

41

39

36

27

30

31

31 32

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Murder trends in Jamaica, Trinidad and Belize 2000-2015

Trinidad

Belize

Jamaica

FIGURE 3

‘WE ARE KILLING OURSELVES

IN UNDECLARED CIVIL WAR’

PUBLISHED: JANUARY 25, 2017